|

How Green the Games?

Athens' Struggle To Host Green-Minded Olympic Games

by Carly West

he Olympics are a big deal; from organizing to producing to watching, there are tens of millions of people involved. Between fifteen and twenty million Americans will tune in each day to watch the events, the athletes, the drama and the sport while the Games are underway from August 13th through the 29th. There are few events that draw more world-wide viewers, and more interest; as such, there is no better stage to spotlight sustainability and sustainable development than the Olympic Games being hosted this summer by Athens, Greece. Ten years ago, Lillehammer, Norway proudly hosted "the first Green Games ever." Now, Athens has the unique and wonderful opportunity to build on the efforts of those before them. They can make a profound and lasting change in their country, and in the world. Are they going to pull it off?

|

| IOC President Samaranch |

The answer to this question is not a simple one; it goes back over two decades and involves thousands of individuals and dozens if not hundreds of organizations. It all began in 1986, when the President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Juan Antonio Samaranch, declared that environment was to be the third pillar of Olympism, along with sports and culture. The idea of producing environmentally-friendly Olympic Games began in 1992 when, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the idea of sustainable development began to gather momentum on the world scene. At the summit, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development adopted Agenda 21, a document drafted by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) that outlines how the world should address sustainable development. This version was adopted by 182 governments in June 1992 and became the springboard for the international community and governing bodies to create an Agenda 21 specific to individual community situations.

Samaranch's declaration made Agenda 21 a very important consideration of the IOC. In 1994, UNEP and IOC joined forces to help make the theory of environment as the third pillar more of a reality, ultimately leading to the creation of the Sport and Environment Commission of the IOC in 1995. Seven years after the original Agenda 21 was adopted, the IOC adopted its own version of Agenda 21 on June 14, 1999, in Seoul, Korea. The entire Olympic Movement adopted the Agenda in October 1999 at the III World Conference on Sport and Environment, held in Rio de Janeiro, where the fateful Earth Summit was held in 1992.

The Programme of Action contained in the Agenda 21 adopted by the Olympic Movement called for (among other things)

- Improving socio-economic conditions,

- Conservation and management of resources for sustainable environment, and

- Strengthening the role of major groups.

Along with the three general categories, the Agenda lists countless ways in which this should occur within the Olympic Games —- everything from the installation of solar panels to using the celebrity status of athletes to launch an educational and informational program to closing down roads into and out of Olympic venues in order to reduce pollution.

At this point, however, the gap between the governing bodies, who signed a lot of paperwork and dreamed up theories to save the planet, and those in charge of implementing the directives of the paperwork and theories was quite large. As is often the case with changing the world, the governing bodies discovered that it took extra money and extra care to implement their new plans, thereby making the theory of "green games" and the reality of producing them very different things.

|

| A full moon illuminates Lillehammer's Green Games. |

In 1994, Lillehammer proved that with the right direction and dedication to the idea, the environmental impact of the Olympics could be lessened, and eventually nearly erased. In Lillehammer's case, this meant using potato-based starch instead of paper products for utensils and plates, initiating widespread recycling programs. Designers and planners took into consideration, among numerous other things, which raw materials went into buildings, how the buildings would be used after the games, and the way in which buildings would blend in with the surrounding natural beauty. These few things only scratched the surface -- the games were "smoke-free" at all indoor areas and tobacco use was discouraged at outdoor venues, private vehicles were not allowed within a 60 kilometer radius of Lillehammer between 6 am and 9 pm, and even the bullets from the biathlon were recycled to prevent local soil from being contaminated with lead.

Interestingly, a lot of what was accomplished in Lillehammer was due to the staunch opposition of residents to Norway hosting the games. They were concerned that the games would have a lasting negative impact the on the environment. Thus, from the earliest stages, the environment and environmental impact was taken into consideration. The independent watchdog group Project-Friendly Olympics played a key role in the results gained in Lillehammer by establishing a four point plan to keep the environment at the forefront of the planning:

- companies were instructed to use natural material whenever possible,

- emphasis was placed on energy conservation in heating and cooling systems,

- a recycling program was developed for the entire winter games region, and

- a stipulation was made that the arenas must harmonize with the surrounding landscape.

|

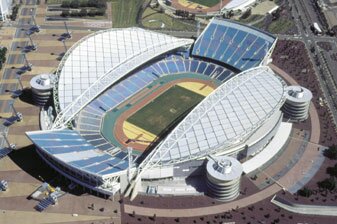

| Sydney's Stadium Australia was built with over 40,000 metres of PVC-free cabling. |

Careful planning and serious concern for the environment proved to be key considerations at the Games in Sydney, Australia six years later. Greenpeace called the effort the "greenest games ever," receiving six out of ten stars in their rating system. Following the general four points laid out by Project-Friendly Olympics and working closely with Greenpeace, the organizers of the Sydney games implemented numerous projects, focusing on reduced energy consumption, solar energy use, and expanding the systems put in place for the Olympics to surrounding areas. For example, Greenpeace was pleased that 665 houses in the Athlete’s Village have grid-connected photovoltaic (PV) solar panels and solar hot water systems, making it the largest solar-powered suburb in the world. The Village’s energy load was 50 percent less than conventional dwellings, saving 7000 tons of carbon dioxide per year. All the successes in Sydney led to the publication of the "Greenpeace Olympic Environmental Guidelines: A Guide to Sustainable Events."

Along with Lillehammer and Sydney, Nagano, Atlanta, Nagano, and Salt Lake City have all hosted the Olympic Games within the past ten years. Armed with much the same information and recommendations as Lillehammer and Sydney, these countries produced games which implemented some of the suggestions for green games, but did not reach the same levels as Sydney did in 2000. Salt Lake City, for instance, had originally proposed to eliminate all private transportation to the venues, but when it came down to it, nearly 30 per cent of the travel to the venues was by private vehicle.

|

| Athens has made efforts to improve its public transportation systems. |

So the saga of the green games has arrived at the present, and the question remains: how green will the games of the XXVIII Olympiad be? Unfortunately, the answer is one that anyone who cares even a little about the environment won’t want to hear. While the environment made it in the mission statement of the Athens Olympics, it is listed eighth out of nine goals for the Games. EnvironmentNepal notes that Athens "won the bid on promise to improve air and water quality, fragile natural and cultural area protection, and traffic and waste management," but also asserts that "Athens equals a step back from Sydney." Athens and the surrounding areas have installed new metro lines as well as enlisting the help of a natural gas bus fleet and a reconstructed tram system. Beyond transportation, there isn’t much to be seen —- there is no evidence of solar power being used, no recycling and waste management program, and the building materials being used have not been classified as non-toxic. While there is still a little time between now and the commencement of the games in August for these improvements to take place, the Athens games have already been chalked up as a failure in the eyes of most environmentalists. Based on Greenpeace's preliminary evaluation of the Games' ability to uphold the third pillar, Athens has received just one star out of ten.

|

| Enviros are worried about the lack of waste management and recycling programs in Athens. |

How is it possible for some countries to produce green Olympics and make such promising strides, and others to fail so miserably? Part of it has to do with the culture and history of the people hosting the games. Lillehammer and Sydney had enormous cooperation and support to produce green games because it was something already valued in their society. Athens, however is a city of nearly three million people, is over 60 percent concrete, and has air pollution problems that rival those in L.A. In addition, there are so many guidelines, regulations, and coming from so many sources (the IOC, UNEP, Greenpeace, etc.) which are all going for the same goal (a green Olympics), but going at it in ways that create struggle between the groups. The biggest issue, however, is that these are just guidelines; there is no absolute rules or laws or anyone to enforce them either. Along with general policy issues, there is an ever-increasing security issue. Reports of problems with security have officials, athletes and spectators alike concerned for their safety; it has thus become a lot easier to shift the focus (and money and resources) away from the environment and toward making the games safe rather than making them green.

Green Olympic Games are much more complex than recycling soda cans and reducing waste, but with all of the implications laid out by numerous governing bodies it seems nearly impossible for everyone to be happy. Olav Myrholt, the Olympic project leader for the Norwegian Society for Conservation of Nature, says, "The only environmentally sound Olympics would be no Olympics at all. Second best would be 'recycled games,' re-using old sites. Lillehammer comes in third." So, this August, as the world witnesses unity via sport, it will unfortunately witness the systematic destruction of the Grecian environment. But there's always Torino 2006.

Carly West writes from Tacoma, Wash.

|

the archives:

Visit the archives, including the premiere edition of

SASS Magazine, featuring Loyalty Clothing, Venture Snowboards, San Francisco's Greenfestival, and so much more.

lillehammer's sustainable strides:

The 10 purpose-built Olympic arenas were constructed using predominately local materials and with strict energy-conserving measures, with a heavy emphasis on post-Olympic use. Some of the arenas will serve as concert halls, a fire station, a golf driving range and a soccer field.

"Visual pollution" was regarded as seriously as air or water pollution. Arenas were built to blend into the natural, surrounding landscape as much as possible; the Cavern Hall was built into the side of a mountain, which, coincidentally, saves about $20,000 in annual heating costs by being inside a mountain.

Contractors were fined almost $7,400 for every unnecessary tree uprooted or damaged.

sydney's sustainable strides:

All competition venues used 100 percent green power for the duration of the Games.

The Athletes’ Village reduced PVC usage by weight against standard industry practice by approximately 70 percent. More than one million meters of PVC-free cabling were used there.

Over 5000 square meters of biodegradable linoleum was laid instead of vinyl flooring at the Media Centre and in the Olympic hotels.

The construction workers' union placed a ban on the use of imported rainforest timber.

|